THE MUSICAL THAT WAS SUNG BY OPERA STARS: WEST SIDE STORY

Reflections on the great Broadway classic

George P. Cassar

Among the New York stage’s many legends, Broadway’s flops take centre stage. Entire books span a wide range of scathing reviews, walk-outs, and box office failures. Many musicals have fallen in the ash heap of history, despite them possessing all the qualities of artistic integrity, originality, the power of the star, and many others for which such a great lip service is being paid.

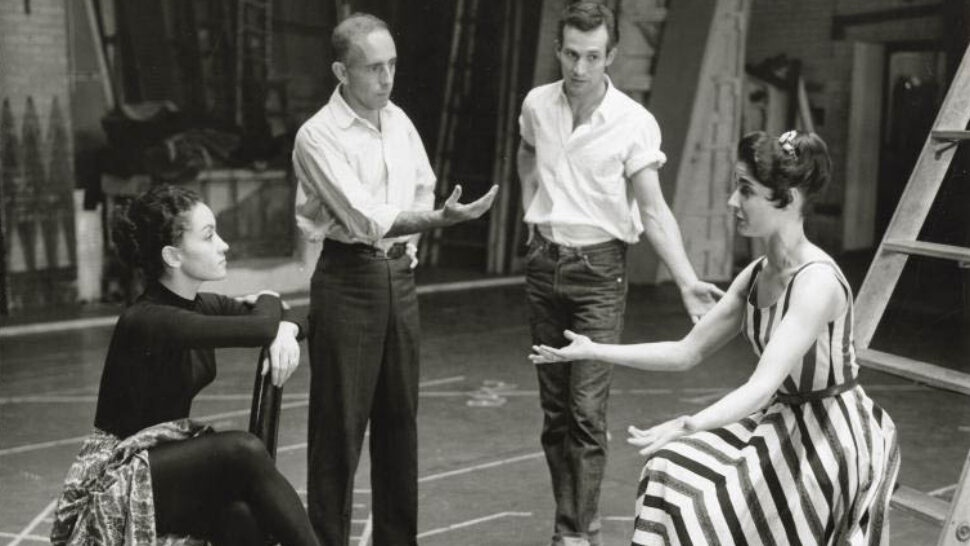

Even though Stephen Sondheim is one of Broadway’s towering figures, some of his shows have not had long runs, both those stemming off his earlier and mature periods. It comes therefore as a surprise that West Side Story, his break as a young lyricist, was not among these. West Side Story could have easily been a commercial disaster. Our familiarity with it makes it difficult for us to imagine how dubious the qualities of the original concept were. It could have easily become dated, since it is based on an acutely stereotypical subject. It exploited a Hispanic style which was already very much overused by that time. As Sondheim himself revealed, the four middle-class privileged men who wrote West Side Story [U1] “had never even met a Puerto Rican”. The tragic and dark tale of juvenile working-class delinquents would not have been funny, nor would it have dealt with social ills in any way. It’s original title was to be Gangway!, and the setting was originally intended to be dominated by warring Catholics and jews in a modern-day Romeo and Juliet. In addition, the show was not intended to feature any stars. with The cast, consisting primarily of dancers, according to New York’s press at the time, was not to be pulled from the dance rehearsal halls, but would have rather consisted of inexperienced dancers. Topping it all, the score, written by a classical music conductor, would sound dissonant in Broadway’s theatres. It would have been diabolically difficult to play and sing, and of all things, would also include a fugue. One could also mention the teenagers’ dialogues that were scripted by a middle-aged Jewish playwright in an invented slang. Given the context in which the show was going to be staged, these elements could have been a perfect recipe for disaster. It is unsurprising that despite repeated attempts, the initial backers’ meeting failed to attract investors for producer Cheryl Crawford. Consequently, Crawford abandoned the production shortly before rehearsals were set to commence. Nobody thought the project would succeed, which leads to the question, why did it? And more importantly, how did it manage to carve itself in American culture almost as no other musical, paying its investors 640 percent within the initial fifteen years?

The fact that West Side Story is featured in two music history textbooks—A History of Western Music by Peter J. Burkholder and A History of Music in Western Culture by Mark Evan Bonds—implies that the musical’s significance in Western culture aligns with the selection of works deemed important by musicologists focusing primarily on classical traditions in music history. Yet West Side Story has been given any overexposure over the years either, since a successful Broadway revival in 2010 that has lured audiences away from all the other shows that boasted bigger stars and more contemporary popular musical styles suggests otherwise, since it demonstrated that audiences are still attracted to the musical.

Most of us have familiarised ourselves with West Side Story through several sources, and thus our reception of the musical becomes a collaboration between us and the various versions which eventually form our collective memory of the piece. These versions, most prominently include the stage performances, especially in their recorded formats, Bernstein’s own dance suite entitled Symphonic Dances from West Side Story known today as part of the standard concert repertoire, the film version which is central in the wider dissemination of the musical, and various recordings of the songs that form the musical, mostly the composer’s own heavily operatic version featuring Jose Carreras and Kiri te Kanawa, as well as the choreographer’s all-danced West Side Story Suite, both of which are attempts at extracting each one’s work from the collaborative process. However, most of our knowledge stems from the various songs that have embedded themselves so much in international culture, either from the aforementioned recordings, or from the countless renderings by other artists, that they have become plucked from their original context and yet are still immediately identifiable. Considering that the songs were dubbed as unsingable by Columbia Records in the 50s, this is deeply ironic.

As Wells (2010) puts it, the reason for the musical’s success is its success in merging social issues, pertinent both when it was written and today. Issues such as the split between the heavily emerging rock music and the traditional musical theatre, the tensions between the traditional and modernist styles within classical music, issues of borrowing and pastiche within supposedly original music, the gendering of ethnicity and musical styles, the role of the musical theatre composer within popular and classical music, and the importance of finding new avenues for the dissemination of musical theatre. These issues expand to wider implications such as ethnic intolerance and stereotypes, the role of feminism, the role of the musical in shaping our idea of American culture and society, the perceived split between the emergent popular music and the more traditional music and the respective socioeconomic status of their attendees, the opposing views between the old and the young, the neophyte and the connoisseur, and the urban and rural theatre goers. In understanding this, we can see West Side Story as a product of its own time, as well as its continued relevance in the contemporary context.

Bernstein, although more known in his role as a conductor, has his own agenda as a composer revealed through his writings on the Great American Opera. Indeed, Sondheim often commented on the way in which he prided himself on having created the great musical, and although this greatness is perceived by the public as having come from its originality, a closer study of the work suggests that much of its fascination lies in its disunities. Indeed, a detailed look at the score reveals substantial ‘borrowings’ from other composers, both in style and content. This may stem from Bernstein’s deep knowledge of repertoire which he gained through conducting, and his formidable memory that enabled him to play anything on the piano from memory.

The composer’s vision of the work, however, rubs harshly against our perception of West Side Story. The prevailing perception that we have embedded in our collective memory is that it is another musical in the same style as the rest. As a matter of fact, Leonard Bernstein released his definitive version of the work with a handpicked orchestra and the opera singers whom he wanted to be singing West Side Story. This recording was often critically received, yet this is not because that performance of Jose’ Carreras and Kiri Te Kanawa were inadequate, but because we often want to rob this musical from the composer’s own hands and give it our own stylistic ideas.

As Jerome Robbins claimed in the Dramatists Guild Quarterly of 1985, what was important about West Side Story was that the musical was conceived by merging the Sondheim’s expertise as a playwright and who aspired to produce a ballet, and Bernstein who wanted to write an opera. Fusing these talents and aspirations together was central in producing the show that we know so well today.

One cannot exclude Bernstein’s ‘magic touch’ from the musical’s successful recipe. Take “Le Sacre du Printemps ”, which is supposed to be the work that revolutionised music and changed the world, and just analyse it page by page, bar by bar. You’ll find that every bar of it comes from somewhere else. But it has just been touched by this magic guy” (interview by Paul R. Laird with Bernstein, 1991). Knowing this, we can say the same thing for West Side Story, since upon a deeper analysis of the score, one notices that many elements of the music hail from other sources, however by becoming aware of these borrowed elements, we can understand better the ‘magic guy’ that Bernstein himself was.

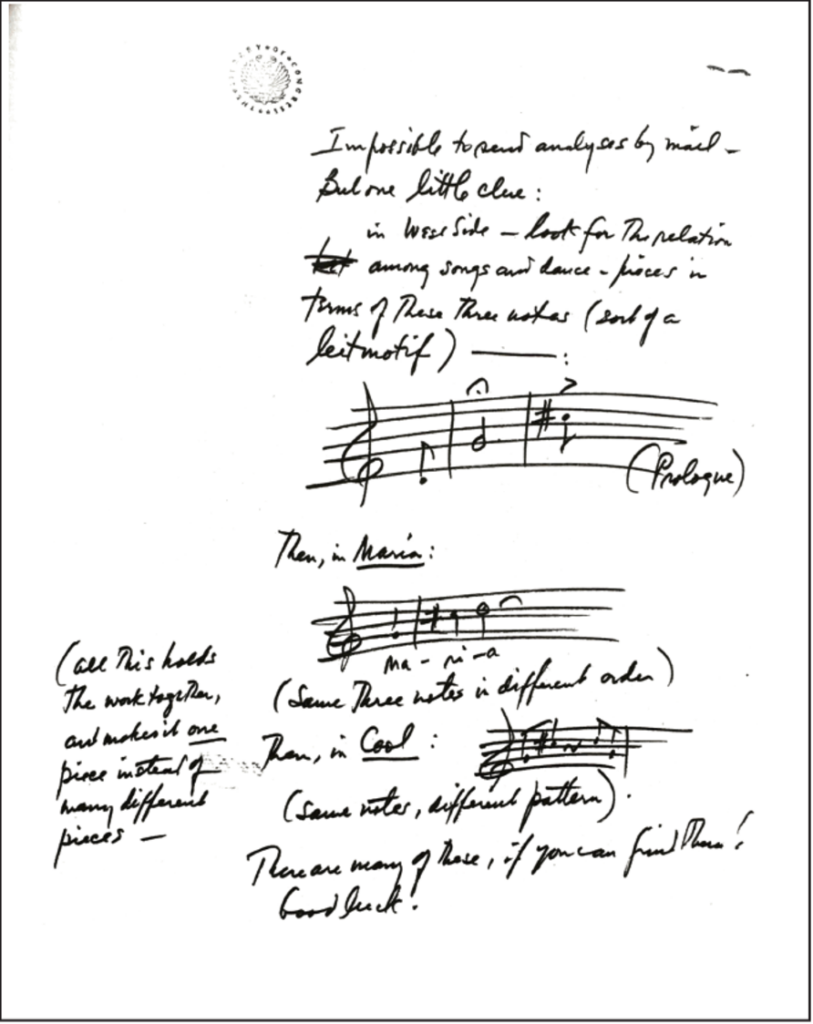

Clearly, Bernstein’s score caters to the many demands necessitated by Robbins’s choreography. However, its originality lies mostly in its modernity in terms of its complexity and treatment of dissonance, along with its complicated and colourful orchestration, and the unity achieved through the use of leitmotifs. These are mostly used to unify the relation between songs and dance pieces, using the same tritone in a different pattern. This is what holds the work together making it one piece instead of a set of different disconnected pieces. This approach of using leitmotifs and the tritone in western music harks back to the nineteenth century, which, by 1957 could hardly have been progressive or modern by any standard. Yet, to the Broadway audience, the dissonance that emerges from the music came out to be much more avant-garde than much of the music written up to that point in that genre.

This, along with the tight integration of dance, drama, design, and music, signalled a sort of turning point in musical theatre. These are the aspects that make the musical a singular organic piece. Indeed, even Sondheim said that “what the critics didn’t realise – and they rarely realise anything – is that the show isn’t very good. By which I mean, in terms of individual ingredients it has a lot of very serious flaws: overwriting, purpleness in the writing and in the songs, and because that characters are necessarily one-dimensional” (quoted in Secrest, 1998). Despite this, since the musical is an integrated work, it continues to dominate. Nevertheless, the musical maintains its stronghold on the musical consciousness, widely perceived as a unified and coherent creation. However, examining the musical through Bernstein’s various frameworks unveils the depth of the piece and offers an alternative approach to interpreting West Side Story as a collaborative endeavor in musical theater.

Eclecticism is another important point in the musical’s success. As Bernstein (1973) himself put it in his series of lectures at Harvard Unanswered Questions, speaking about Stravinsky, he says “he was a facile virtuoso, a clever vaudevillian, a talented ballet-composer parading as a symphonist, a thieving magpie and – the most unforgivable sin – he did not restrict his thieving; he was an eclectic. He wrote music about other music”. When asked whether one must base his work on what has come before by Paul Laird in 1991, Bernstein answered “otherwise, you don’t exist”. He then goes on the cite Le sacre du printemps as an example of groundbreaking music based entirely on music that has preceded it. So does this place Bernstein in this legacy?

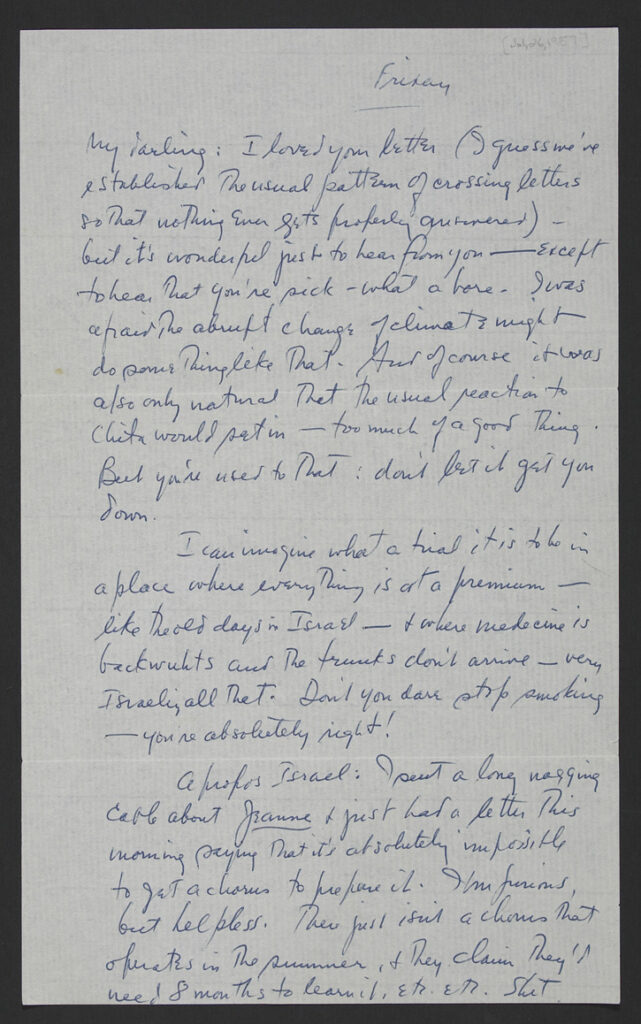

Bernstein has left several writings about his aspirations and issues as a composer. West Side Story, falling as it did at his ascendancy as a musical personality, definitely held a special place in his development by addressing his inner conflict between being a composer or a conductor. Writing to his wife Felicia in 1957 just a few weeks before the opening of West Side Story for previews, Bernstein says “the show -ah, yes. I am depressed with it. All the aspects of the score I like best – the “big’, the poetic parts – get criticised as “operatic” – and there’s a concerted move to chuck them. What’s the use? The 24-hour schedule goes on – I am tired and nervous and apey. You wouldn’t like me at all these days. This is the last show I do. The Philharmonic’s board approved the contract yesterday, and all is set. I’m going to be a conductor, after all!”

While it’s evident that the collaborative process exacted its toll on the composer, the subsequent popularity of the work solidified its association with Bernstein’s music, thereby complicating his internal conflict between conducting and composing. David Diamond (2002) recalls, “when he came to Florence we were in the piazza, and from all the loudspeakers came this song, Maria. It just took over every place in the world including the Soviet Union. And, typical Lenny, he said “Oh, that’s me ””.

Many will note similarities between West Side Story and music from other composers that Bernstein invoked in the name of eclecticism. ‘Tonight’, the quintet, may be modelled on the Mozart ensemble finale, and with Bernstein having such a wide background as an operatic conductor, even debuting as the first American conductor at La Scala in 1953, he may well have used the model as perfected by Mozart for his ensemble. His modulations however, are much more restricted, and this is understandable considering the vocal ranges that he had to work with at the time. Other operatic models can include the quarte in Rigoletto, and the quintet in Wagner’s Meistersinger.

Wells (2010), highlights how one of the most notable instances in Bernstein’s Harvard lectures, where we get a further glimpse into his life as a composer, is the example of a Chopin mazurka that he discusses in his lecture titled “The Delights and Dangers of Ambiguity”. In this lecture, Bernstein examines Chopin’s Mazurka op. 17, no. 4 as a prime illustration of both tonal and rhythmic ambiguity, two characteristics also found in West Side Story. The first bars of “Maria” reveal a similar ambiguity, featuring a parlando-style introduction to the song that shares the triplet subdivision of the beat present in Chopin’s piece. The parallels are striking, particularly as the conclusion of Chopin’s mazurka, which Bernstein highlights in his Harvard lectures, bears a remarkable resemblance to the opening bars of “Maria”. Moreover, the initial rendition of the song was transposed up by a minor third, aligning this section originally with the same pitch class as Chopin’s composition. Although the decision to lower it appears logical due to Larry Kert’s vocal limitations and criticisms from other collaborators about Bernstein’s music being “too operatic,” the intention behind the song was not only to mirror Chopin’s tonal structure but also to incorporate the high C climax characteristic of operatic tenors, and not necessarily those in Broadway productions. While the original, more operatic rendition was adjusted to suit the demands of the Broadway stage, Bernstein initially envisioned this moment as a more operatic expression with deeper classical roots.

Wells further discusses how Bernstein’s “borrowing” suggests more than mere inspiration from another composer. It goes beyond this: the ambiguity present in Chopin’s piece, as noted by Bernstein in his lecture, is enhanced, or “resolved” in Bernstein’s own composition. The conclusion of the mazurka, singled out by Bernstein as leaving the listener “hovering as we began, in the bliss of ambiguities”, continues and finds completion in “Maria” with the cadence in measure 11: here, the E-flat chord transitions to a B major chord (F to C major in the original key), accompanied by an accented lower neighbour on the word “Maria”. Thus, in the listener’s perception, something vaguely familiar, something “hovering,” finds resolution and continuation in Bernstein’s work—a resolution that is satisfying not only because it addresses or resolves a harmonic ambiguity, but also because it advances the lyrical narrative, “Maria, I’ve just met a girl named Maria.” This lyric is repeated and intensified by the repetition of the girl’s name, just as the harmonic and melodic foundation propels that moment forward. This serves as a remarkable instance in which an allusion to another work evolves into a new composition. It’s an almost alchemical moment, entirely belonging to Bernstein, as “Maria” was composed before the rest of the musical, with both lyrics and music crafted by the composer.

The connection to Chopin, although brief in its duration, is far from coincidental. Just a year after the premiere of West Side Story, Bernstein utilized the Chopin mazurka genre as a reference point to explore the interplay between word meaning and music meaning. In an article for The Atlantic (1957), he pondered, “If it were possible for words to ‘tell’ a Chopin mazurka—its sad-gay quality, the abundance of its brevity, the polish of its detail.” This exploration of the relationship between words and music, and the inherent meanings within them, was a significant aspect of the perceived unity in West Side Story. Bernstein’s discussion of Chopin outside the context of the musical delves into broader questions of musical harmony and ambiguity. For him, it signifies the onset of the kind of ambiguity that characterises the twentieth century and will ultimately find its culmination in Stravinsky.

Berlioz and, as already mentioned, Wagner, play another important part in the structure of West Side Story, a structure that runs throughout the entire work. In fact, one can theorise that Berlioz’s Romeo and Juliet must have been constantly ringing in Bernstein’s mind when he sat down to write West Side Story. It is not one of your usual symphonic pieces, and is sometimes classified as a semi-opera, however, it was a favourite in Bernstein’s repertoire. As far back as 1950, a performance prompted a fan letter from fellow musical theatre composer Marc Blitzstein, who described Bernstein’s interpretation as evoking “a beautiful sober romanticism, an innate tragic sense.” Bernstein later toured the work with the Israel Philharmonic in Italy in 1955, pairing it with his own composition, Serenade, which also explored aspects of love. Within a few months of the tour, he agreed to work on a musical play titled East Side Story with Arthur Laurents. The thematic similarities between Berlioz’s treatment of the Shakespearean tale and Bernstein’s work were notable, both starting their compositions with a prologue depicting the war between rival factions. The fugal texture of Berlioz’s opening finds reflection in Bernstein’s prologue, as well as the climactic moment—the intervention of the prince—that halts the action. Interestingly, Berlioz’s warring prologue includes text, reminiscent of the original “Prologue” for West Side Story, which was later abandoned due to difficulties in performance. This decision could be seen as an attempt by Bernstein to modernize Berlioz’s approach.

Another point of comparison lies in their use of leitmotifs. Both composers employ reminiscence motives and leitmotifs, integrating scenes through instrumental music. In West Side Story, crucial scenes such as the “Prologue,” the “Dance at the Gym,” and the “Rumble” are musically dramatized without traditional Broadway songs. Similarly, in Berlioz’s work, important scenes are expressed solely through orchestral music.

Furthermore, both composers refrain from giving vocal parts to the protagonists, instead favouring the chorus or other characters. Berlioz’s “Strophes” for female solo and Bernstein’s use of “Somewhere” fulfil a similar function in exploring the nature of love and central themes. Additionally, Berlioz’s wordless vocalisation in the last movement of Romeo and Juliet finds a parallel in the truncated reprise of “Somewhere” that concludes West Side Story.

Daniel Albright (2001) remarked that Romeo and Juliet became “one of the most generically challenging works of the Nineteenth Century”, which perhaps explains why this work required the input of Bernstein in the 1950s for it to become popularised as part of the standard classical concert repertoire. West Side Story was also a new genre of musical theatre, unclassifiable within the pervious standards, echoing the nature of Berlioz’s work a century before. Perhaps Bernstein wanted to improve upon his favourite works and rewrite them for the new era. Bernstein’s hero Tony, in fact, is not the euphoric dreamer as the nineteenth century Romeo. He is enveloped within a ‘cool’ modern aesthetic, something that characterises West Side Story throughout, making it an extension of the great tradition, but also adopting a modern twist.

Inevitably, the question of whether West Side Story is a musical or an opera, crops up. It is interesting to know that Bernstein considered his failure to make West Side Story more operatic quite personally, and this cannot be simply explained to be the result of cutting back on his operatic music by the other collaborators, although his writings in 1957 to his wife suggest that this was an issue as well: “In a minute it will be August, and off to Washington—and people will be looking at West Side Story in public, & hearing my poor little mashed-up score. All the things I love most in it are slowly being dropped—too operatic, too this & that. They’re all so scared & commercial success means so much to them. To me too, I suppose—but I still insist it can be achieved with pride. I shall keep fighting”. He perceived his failure to put Maria’s final speech to music as another major contributor to this. He explains it himself this way: “At the denouement, the final dramatic unravelling, the music stops, and we talk it. Tony is shot and Maria picks up the gun and makes that incredible speech, “How many bullets are left?” My first thought was that this was to be her biggest aria. I can’t tell you how many tries I made on that aria. I tried once to make it cynical and swift. Another time like a recitative. Another time like a Puccini aria. In every case, after five or six bars, I gave up. It was phony” (Stearns, 1985). Even Laurents, his collaborator augments this argument, quoted from the same source as saying “We all hold certain set beliefs, and I’ve always believed that the climax of a musical should be musicalized. Well, the climax of West Side Story is not musicalized. It’s a speech that I wrote as a dummy lyric for an aria for Maria, with flossy words about guns and bullets. It was supposed to be set to music, and it never was.”

While Bernstein’s familiarity with the classical repertoire undoubtedly influenced his stylistic and structural choices, it was the music of his contemporaries and immediate predecessors that elicited the most compelling responses from him as a composer. In his quest to compose the Great American Opera, Bernstein naturally turned to Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess, one of the significant American operatic achievements of the 1930s, as his primary model. Not only did this work strive to bridge the gap between opera and Broadway, but it also broke new ground by blending operatic styles with contemporary vernacular, particularly that of African-Americans. This relationship was also deeply personal for Bernstein, reflecting his affinity with Gershwin’s background and aspirations as a composer. In “Why don’t you run upstairs and write a nice Gershwin Tune” of 1978, Bernstein expressed admiration for Gershwin’s musical prowess and his impact on American urban culture, considering him one of the greatest composers of the century.

Bernstein particularly acknowledges Gershwin for achieving what he himself aspired to: transitioning from creating mere shows to crafting substantial theatre pieces. Reflecting on his youth, Bernstein admits to initially taking Gershwin’s work for granted, familiarising himself with his shows, but it was Porgy and Bess that profoundly impacted him. Recalling his experience as a freshman at Harvard when Porgy and Bess premiered in Boston in 1936, Bernstein recounts being captivated by the production, despite being unable to afford the music initially. However, he eventually acquired a score and immersed himself in its entirety, having already absorbed its melodies through repeated listening.

Unsurprisingly, Porgy and Bess served as a significant influence on Bernstein’s own compositions, not only in terms of its musical elements but also in shaping his conception of comprehensive artistic works. The societal divisions depicted in Porgy and Bess, between African-American and white communities, parallel the thematic exploration in West Side Story, where the divide is represented by the clash between adult and teenage worlds. This parallelism is evident in the police interrogations portrayed in both works, as seen in the comparisons between Heyward and Laurents’ narratives in Porgy and Bess and West Side Story.

Just as Gershwin distinguishes between the two groups by having the African-American characters sing rather than speak, the creators of West Side Story restrict singing and dancing to the youthful protagonists. Both scenes depict a similar sense of tension and resistance against police authority, with the detectives becoming frustrated by the interviewees’ lack of cooperation. The tactic of feigned illness, used by both Maria and Serena to avoid testifying, creates a dramatic parallel, as seen in the initial interrogation at Robbins’s funeral. Additionally, both works were originally conceived as three-act compositions, akin to Porgy, although Robbins intervened early on to streamline West Side Story into the standard two-act Broadway format. Furthermore, Gershwin’s use of Crown’s motif during the storm scene of act 2 foreshadows Bernstein’s treatment of leitmotifs in the orchestral sections of West Side Story, particularly the recurring “Maria” theme. Individual songs in both works exhibit similarities, with Maria’s “I Feel Pretty” mirroring the sentiment, style, form, and placement of Porgy’s “I Got Plenty o’ Nuttin’,” showcasing a contented feeling in their respective contexts. Despite feeling Gershwin’s influence and the weight of the classical tradition, Bernstein’s creativity as a composer was deeply influenced by Igor Stravinsky’s music. Bernstein frequently responded to Stravinsky’s work in his own compositions, recognising Stravinsky as one of the most significant composers of his time. Stravinsky’s ability to imbue every note with his unique style and his wide-ranging musical expressions resonated deeply with Bernstein’s artistic aspirations, exemplified by West Side Story‘s enduring legacy.

In the early 1950s, Stravinsky’s opera “The Rake’s Progress” and Bernstein’s “Candide” emerged as political and allegorical works drawing inspiration from eighteenth-century morality tales, reviving baroque operatic styles and forms. While it is uncertain if “Candide” was directly influenced by Stravinsky’s work, it aimed to master the genre in a distinctly American, eclectic manner, soon after Stravinsky’s endeavours. With “West Side Story,” Bernstein sought to revolutionize musical theatre, influenced in part by the balletic elements introduced by Robbins, possibly prompting Bernstein to contemplate Stravinsky’s balletic legacy.

Bernstein’s descriptions of Stravinsky in his Harvard lectures mirror his own approach to crafting self-styled primitivist music, such as the “Rumble” or the “Prologue” from “West Side Story,” where vernacular music is infused with what he terms as “stylish sophistication.” Stravinsky’s primitivism, however, achieves its most notable effects through the juxtaposition of modern sophistication with ancient themes, presenting a captivating tension between twentieth-century composition and prehistoric subject matter—a vibrant blend of earthy vernacular and stylistic refinement.

The most significant connections between West Side Story and Stravinsky emerge in Stravinsky’s “The Rite of Spring,” a piece Bernstein often hailed as revolutionary in music. The ritualistic and tableau-focused nature of this ballet aligns well with Robbins’s visceral choreographic style, and the theme of rites of passage, mirrored in scenes like the “Dance at the Gym” and the “Rumble,” resonates with Stravinsky’s work. Bernstein’s rhythmic experimentation in West Side Story, such as the shifting accents in the rumble, echoes Stravinsky’s rhythmic displacement in sections like the Augurs of Spring.

If West Side Story attempts to rewrite musical history or revolutionise Broadway, then Bernstein’s “improvement upon” Stravinsky lies in the integration of elements, achieving a kaleidoscopic or cinematic quality, as noted by the collaborators. This quality was accentuated by the film medium, which played a significant role in the late 1950s. Moreover, moments where Bernstein channels Stravinsky the most, lead to transitions into new musical territories, as seen in the abrupt shifts from Stravinsky’s influence to original motifs in West Side Story.

Bernstein’s reverence for Stravinsky goes beyond musical emulation; it extends to Stravinsky’s role as a saviour of tonality in the early 20th century. Bernstein, a proponent of tonality, saw Stravinsky’s innovations as vital in preserving this tradition. Through works like West Side Story, Bernstein aimed not only to echo Gershwin’s “final amalgamation” in Porgy and Bess but also to demonstrate that tonality could endure indefinitely, revitalised by talented composers. Bernstein aspired to be counted among these great composers, grappling with his identity as a composer throughout his life.

Among all the borrowings and influences present in West Side Story, it is these echoes that Bernstein reflects on in his later years, which continue to captivate audiences and musicologists, serving as a subconscious nod to the sources that likely shaped his most impactful (and arguably, his finest) composition.

In either case, Bernstein’s manipulations of previous models, whether subtle or overt, have imbued West Side Story with a rich tapestry of memorable moments drawn from the canon of Western classical music. Beyond mere homage, Bernstein’s own reflections on music, disseminated widely to generations of music enthusiasts, serve as a retrospective justification for his compositional output, making him a kind of apologist for his own compositional output, acting as a lens through which the classics are interpreted and filtered. Bernstein subtly presents and reinforces “West Side Story” to the audience by incorporating a repertoire that draws from sources beyond the realm of music.

Viewing the musical through this lens prompts the question: does it emerge as a unified, organic, and modernist piece, or is it perhaps a postmodern opera, relying extensively on intertextual allusion to become a masterpiece of eclecticism? Bernstein’s creative process, fuelled by an exceptional memory and fluency in music across periods and styles, allowed him to seamlessly integrate gestures from a broader musical language, often explaining his choices retrospectively. This raises the question: was Bernstein one of the earliest postmodern composers?

Despite Bernstein’s aspirations for West Side Story to attain a more operatic status, evidenced by his efforts to include operatic elements such as a prolonged balcony scene that includes a recitative section, and his high Cs in Maria and Anita’s duet among many others, the reality of his dual roles as composer and conductor weighed heavily on him, especially during the 1970s. The pressure to secure a place within the classical tradition, combined with his dwindling compositional output and the realisation that he might not achieve his desired level of recognition as a composer, created internal conflicts. Bernstein’s desire for acceptance as a classical composer clashed with the cultural perceptions that favoured opera over Broadway, exemplified by Laurents’ observation that the culture often regarded opera as art while dismissing Broadway. Despite his pedigree, Bernstein’s inner struggle between being recognised as an art-music composer and an aspiration to be the next Gershwin and Diamond, remained evident both within West Side Story and beyond.

In essence, while Bernstein’s diverse influences showcased his torn aspirations, West Side Story ultimately stands as his greatest musical achievement, perhaps hindered by his own inner conflicts from being acknowledged as his great American opera.

References

Albright, D. (2001). Berlioz’s semi-operas : Roméo et Juliette and La damnation de Faust. University Of Rochester Press.

Bernstein, L. (1957, July 28). Personal correspondence between Bernstein and his wife [Letter to Flicia Montelaeagre Bernstein].

Bernstein, L. (1957). Speaking of Music. The Atlantic, 200, 104–106.

Bernstein, L. (2002a). The Unanswered Question : six talks at Harvard. Harvard University Press.

Bernstein, L. (2002b, July 14). [Interview by E. A. Wells]. In West Side Story : Cultural perspectives on an American Musical.

Elizabeth Anne Wells. (2010). West Side Story : cultural perspectives on an American musical. Scarecrow Press, Inc.

Laird, P. (2015). Leonard Bernstein: Best of all possible legacies. Routledge.

Meryle Secrest. (2011). Stephen Sondheim : a life. Vintage Books.